Gateway 2 and 3 - Industry reaction

Introduction

This article is a follow-up to my previous article about Gateways 2 and 3. The previous article was a summary of what I see as the main impacts that the Gateways will have on fire engineers. It identified concerns that some of the procedures that the Building Safety Regulator (BSR) is following (in particular the lack of any pre-consultation) will likely result in a very high rejection rate.

This follow-up article is focused on how the industry appears to be responding to the new regulations. In summary, there is huge variation.

The BSR, and many others in the industry, have made considerable effort to publicise the new regulations, but with the best will in the world, that’s only ever going to reach a proportion of the industry.

Some project teams are putting in huge effort to understand and comply with the new rules, but others just seem to be ignoring them, which is likely to turn out very badly for anyone involved in those projects.

As for the previous article, the issues summarised below are my views, based on my experience of working within the industry, including discussions with other fire engineers and with the BSR.

Current Gateway 2 applications

The new regime has been in place since 1 October 2023. I have heard from the Building Safety Regulator (BSR) that the only applications that have been received since then have been for work on existing Higher Risk Buildings (HRBs) and that no applications have been received for new-build HRBs yet.

That isn’t particularly surprising, primarily because the new Gateway 2 process will require the initial application to have a much more detailed design than would have been the case under the previous regime. This will take several more months, and possibly longer, before the design is at the point where it could be submitted.

So, if a particular new-build project has developed the design to the point where a Gateway 2 application can be submitted now (i.e. January 2024) in practice, the design would probably have been submitted under the previous regime prior to 1 October 2023. This means that the only new-build Gateway 2 applications that the BSR is likely to receive in the next few months are likely to be from clients and design teams that haven’t understood the Gateway 2 regime.

If the project team have misunderstood the regulations to that extent, they’ve probably got plenty of other things wrong as well. So, in the short term, any new-build applications are likely to have a very high rejection rate, purely due to inadequate applications.

I would also note that feedback from the BSR is that some of the applications that they have received don’t include all the required documentation. As noted in the BSR Guide, Gateway 2 applications need to include a specific list of documents, such as Competency Declarations and Construction Control Plans. If those aren’t included in the application, it won’t even be accepted onto the system. The fact that applications don’t include those documents suggests that the clients and design teams for those projects have not spent the time and effort to investigate the new regulations, which probably means that the applications will not meet the requirements and will result in a very high rejection rate.

New-build applications

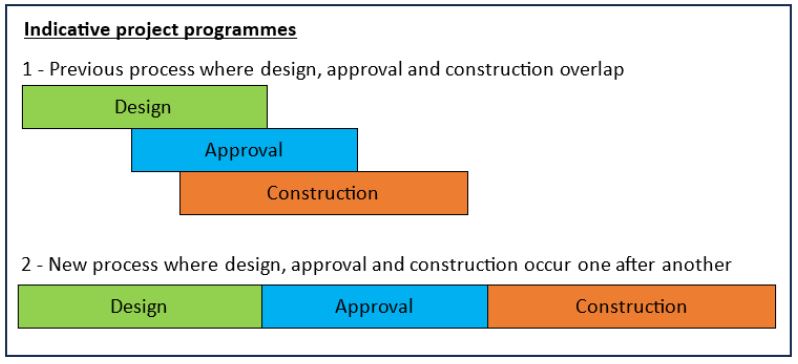

As noted in my previous article, for new-build projects one of the fundamental aspects of the new Gateway 2 and 3 regulations is to change the way that the design and approval process works. Current practice is that the initial Building Regulations application would be a relatively early stage design, with more design carried out, and further details to be submitted in stages as the design progresses. Construction would usually start whilst parts of the design and approval are still being resolved. That is no longer going to be acceptable.

The principle will be:

1. Do the design;

2. Get the design approved;

3. Build to the approved design;

4. Occupy the building.

Each of those will be a specific stage, and it will no longer be acceptable to have any overlap between those stages. In particular, it will be illegal to start building before the design is approved, and it will be illegal to build anything other than the approved design.

This will have an enormous impact on the industry, which is used to starting work on site whilst a large amount of the design and approval are still being worked out.

The previous process has the advantage that it is fast. Construction starts well before the design is finished, and quite a lot of the detailed design (and the approval for that design) occurs whilst the construction is ongoing, which means that the construction starts and finishes relatively quickly.

Obviously the downside of the previous process is that comments may be received from the approving bodies on something which might have already been built. For example, if Building Control or the Fire Service disagree with the design of a smoke ventilation system, and the comments are only received after the system already been installed, then that creates a difficult problem, both for the design team and for the approving bodies.

The new process is going to make sure that doesn’t happen. Construction can only start once the design has been completed and approved.

However, the downside is that the new process will result in much more time needed for the whole design/approval/construction process. This is shown indicatively in the image below.

The construction industry is used to large overlap between those three stages, and project programmes are based on that. Time is money, and so delays to the construction programme will have a large impact on the project finances.

Industry response

So, one of the key factors for the new regime will be how the industry responds to this change.

As noted earlier, many developers, designers and contractors have spent a considerable amount of time familiarising themselves with the new regime. On the other hand, many have not.

I have recently heard of two projects where the client has instructed the design team to make a Gateway 2 application at the end of RIBA Stage 3, with the intention that the RIBA Stage 4 design process will continue whilst the Gateway 2 application is under way. Both of those are large projects, with professional design teams (although I’d note that my company isn’t working on either of them). Clearly the approach that the client is instructing is completely in breach of the Gateway 2 process described above.

Presumably those Gateway 2 applications (when they do occur) will go badly wrong. They may be rejected due to the design being at the wrong level of detail. Or if the BSR does review (and eventually approve) the design, the contractor will have a problem that they now have to build to the approved design, despite that it’s only at RIBA Stage 3. If they build anything different from the approved design, it’s a criminal offence. They can submit Change Control applications for changes to the approved design, but that’s intended for a limited number of specific changes, not a wholesale replacement of the design with a more developed design.

Presumably the client and/or contractor will lose a lot of money because of that, so there’s going to be a risk of legal actions to try and reclaim that. They can’t sue the regulator, so anyone else in the design team is going to be at risk.

Conclusions

My previous article discussed the processes that the BSR is adopting for the Gateway 2 process and raised concerns about how some of them are likely to cause some major problems to projects, in particular the lack of pre-consultation. That on its own is likely to create a high rejection rate.

However, there is also the problem relating to the industry’s response to the Gateway 2 process. Whilst a proportion of the industry has been working to ensure they are aware of the new regulations, there are many in the industry that have not. Any Gateway 2 applications for new-build projects that occur in the next few months are likely to be from clients and developers who are in the latter group, which is likely to result in a high rejection rate. Presumably their design and construction programmes are also very likely to be unrealistically optimistic as well, with work on site only starting a year or more later than they might have expected.

I would recommend that anyone who is working on a project where the client has not understood the new regulations properly should seriously consider the situation. As a minimum, they ought to take measures to protect themselves from the fallout that will occur when the application is rejected and the project is massively delayed.

Combining these factors together, I do envisage a nearly 100% rejection rate for new-build Gateway 2 applications for a year or more. As it will be illegal to start work on HRB projects without Gateway 2 approval, that will mean almost no HRB projects starting on site throughout England over that time. HRBs only make up a small proportion of the overall construction industry, but for any companies that focus on HRB projects, or any areas where there is a higher proportion of HRB projects (e.g. London) that will have a significant impact on construction activity.

In construction everyone is very keen on the ‘blame game’, so presumably project teams will blame the BSR and the BSR will blame the project teams. Both will probably be right to a certain degree, but until the core reasons for the high rejection rate are identified, the problem won’t be solved.

As noted in my previous article, the above predictions are my best guess as to what will happen, and I don’t really know for sure. But that best guess is based on decades of experience in fire engineering, plus quite a lot of time spent understanding the new regulations (including regular liaison with the BSR).